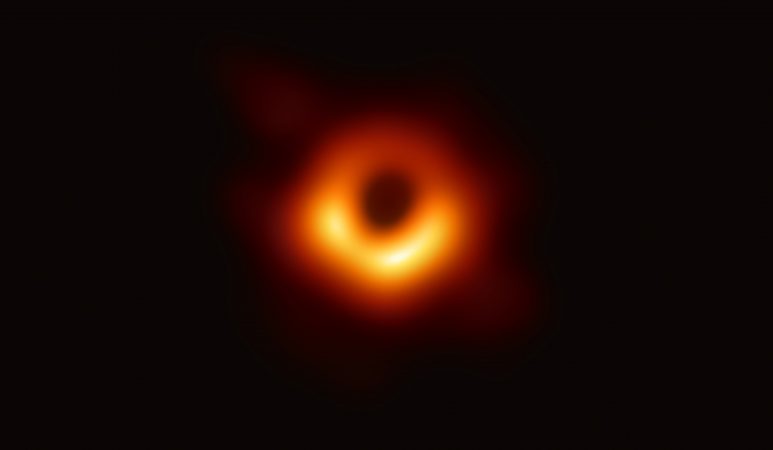

We know that black holes are fascinating objects, capable of bending not only our minds but also reality itself. They squeeze matter into an extraordinarily miniscule space, resulting in an object with an immense gravitational pull. Around this object is a boundary beyond which nothing can escape, not even light: the event horizon. Besides attracting enormous quantities of matter, the event horizon is attracting a lot of attention from astronomers around the world. But why?

As we discovered in the previous post, black holes are impossible to observe directly. Photons aren’t emitted, and therefore nothing reaches the astronomer’s telescope (except, of course, small amounts of Hawking radiation). But scientists can learn a lot from the bright material surrounding black holes.

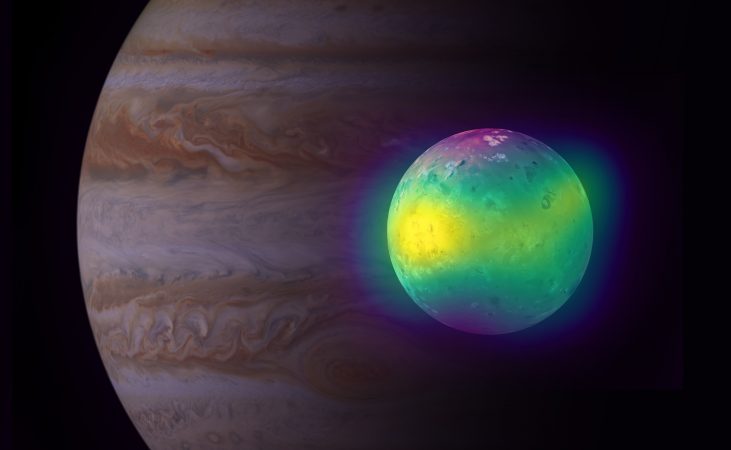

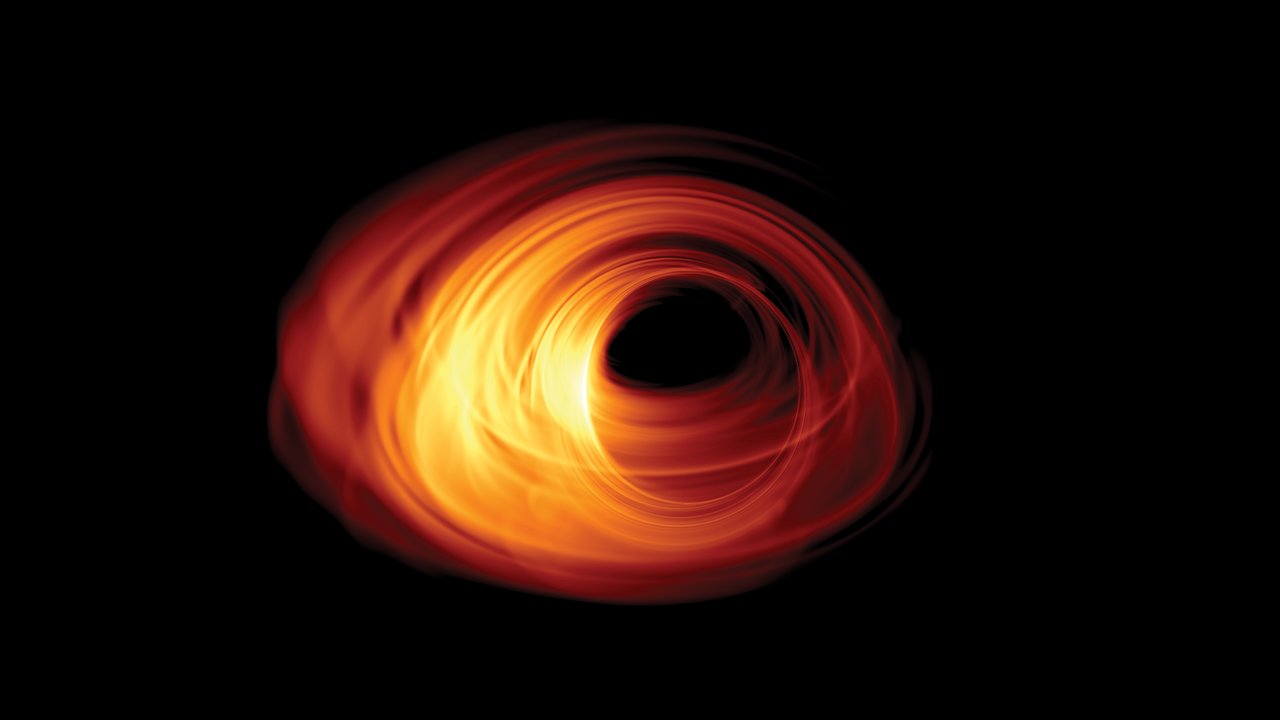

When matter comes under the gravitational spell of a black hole, material will either be sucked directly into it or will be pulled into a doomed orbit like water circling a drain. The gravitational pull near the event horizon is so strong that the matter around it reaches relativistic speeds (i.e. speeds comparable to the speed of light). The friction between the material heats it to incredibly high temperatures, turning it into glowing plasma. Close to the event horizon photons are pulled into nearly circular orbits, and this form a bright photon ring which outlines the black “shadow” of inside the event horizon itself.

Simulated image of an accreting black hole. The event horizon is in the middle of the image, and the shadow can be seen with a rotating accretion disk surrounding it. Credit: Bronzwaer/Davelaar/Moscibrodzka/Falcke/Radboud University

Einstein’s theory of general relativity predicts the existence of event horizons around black holes. But until now, the resolution of our telescopes has not been high enough to “see” a black hole. Despite the fact that the event horizon can be millions of kilometres in diameter, black holes are elusive. They are very far away and often hidden behind significant amounts of interstellar gas and dust. At 26 000 light-years from Earth, our galaxy’s supermassive black hole — called Sagittarius A* — is just a tiny pinprick on the sky.

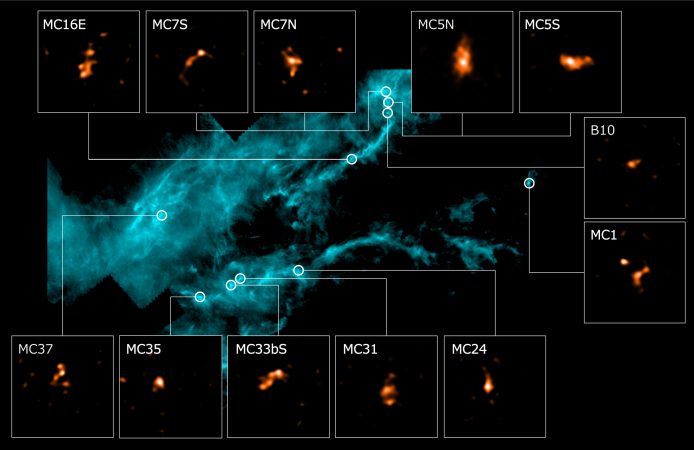

By linking up different telescopes across the globe, the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) and the Global mm-VLBI Array (GMVA) can achieve the resolution necessary to perceive the pinprick of Sagittarius A*. Without doubt, these observations are incredibly exciting. They will allow for the study of black holes in more detail — as well as acting as a test for Einstein’s theory of General Relativity.

“Einstein’s wonderful general relativity has been around for about a hundred years now and is very unintuitive, but despite that, it has managed to overcome all tests so far,” explains Ciriaco Goddi, astronomer from the EHT. “However, these tests have not been done in such strong gravitational fields.”

A pressing issue in physics is that the theories of general relativity and quantum mechanics seem to be fundamentally incompatible. To get to the bottom of this issue, physicists need to study the places where these theories overlap or break down. However, the conventional view is that this will not be observed at the event horizon of a supermassive black hole: quantum effects are expected to be important only near the horizon of lighter (about 10 microgram) black holes — of which we currently have no evidence for their existence. Yet some theorists argue that there will be deviations from classical general relativity close to the event horizon even for supermassive black holes, and these are potentially observable with the EHT.

“If there is any deviation from Einstein’s predictions near the black hole, where gravitation is at its strongest, we would need a new theory of gravity,” Goddi says, “and that means that we would need to describe space and time in different terms.”

General relativity predicts that the “shadow” of a black hole is circular, but other theories predict the shadow could be “squashed” along either the vertical axis (prolate) or the horizontal axis (oblate). Studying the shadow can therefore test general relativity as well as alternate theories of gravity. Plus, since the diameter of the black hole’s shadow is proportional to its mass, observing a black hole’s shadow may allow astronomers to directly estimate its mass.

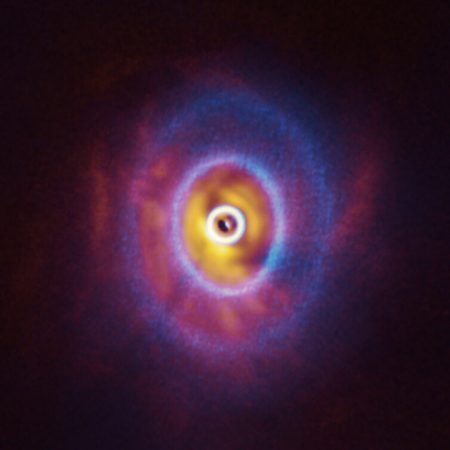

This infographic shows a simulation of the outflow (bright red) from a black hole and the accretion disk around it, with simulated images of the three potential shapes of the event horizon’s shadow. Credit: ESO/N. Bartmann/A. Broderick/C.K. Chan/D. Psaltis/F. Ozel

ALMA astronomer Violette Impellizzeri adds: We think that there is a supermassive black hole at the centre of every galaxy. But the inner workings of these black holes remain a mystery. However, we need to ask ourselves the question of why there is a supermassive black hole at the centre of every galaxy. And it’s become more and more clear that black holes play a fundamental role in the formation of galaxies, and how they evolved. So, the links between the black holes, the galaxies, and the Universe are vital to understand.”

The VLBI observations with the EHT and GMVA will make phenomenal new discoveries, addressing the current and pressing problems of gravitational theory.

This is the fourth post of a blog series following the EHT and GMVA projects. Next time, we’ll explore how radio telescopes work.

![Taking the First Picture of a Black Hole [1] - Attempting the Impossible](https://alma-telescope.jp/assets/uploads/sites/alma.mtk.nao.ac.jp/j/news/files/editor/ann17015a-668x351.jpg)

![Taking the First Picture of a Black Hole [2] - What are the Event Horizon Telescope and the Global mm-VLBI Array?](https://alma-telescope.jp/assets/uploads/sites/alma.mtk.nao.ac.jp/j/news/files/editor/shadow-evt-668x223.jpg)

![Taking the First Picture of a Black Hole [3] - What is a black hole?](https://alma-telescope.jp/assets/uploads/2017/05/2017-04-12_black_holes_infographic-668x473.jpg)