2017.06.21

Taking the First Picture of a Black Hole [6] How to build an Earth-sized radio telescope

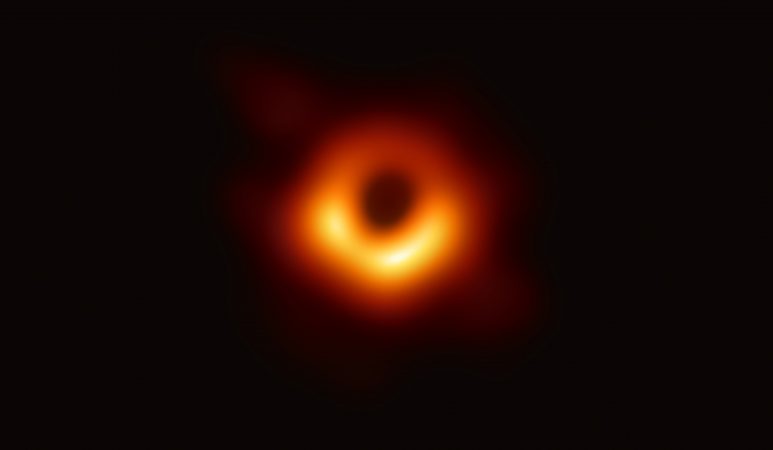

As we discovered in the previous post, the larger the diameter of the telescope, the better the resolution. This is true both for optical and radio telescopes, which means that a tremendously large telescope is needed to observe a small object that can barely be seen from Earth — like a black hole.

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), which is operated in Chile by a global partnership, combines multiple antennas spread over distances from 150 meters to 16 kilometers. This allows it to simulate a single giant telescope much larger than any individual dish that could be built, achieving a resolution equivalent to up to a 16-km diameter telescope. ALMA’s resolution reaches 1/100 of 1/3600 of a degree angle — 5000 times better than the human eye!

And yet even with such an exceptionally good “eyesight”, ALMA would need to improve its resolution 100 fold in order to capture a black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy.

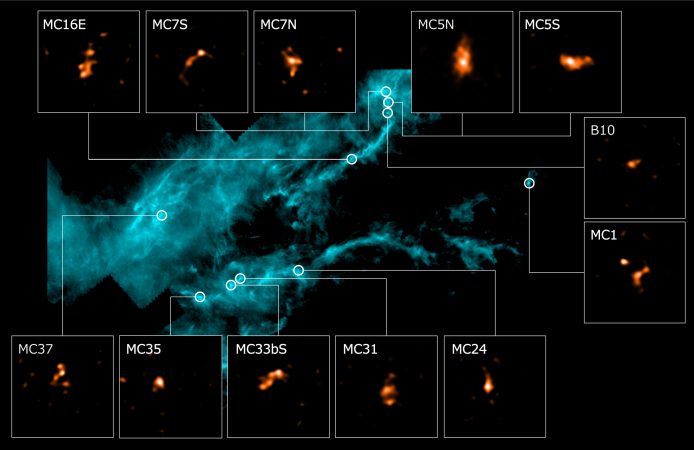

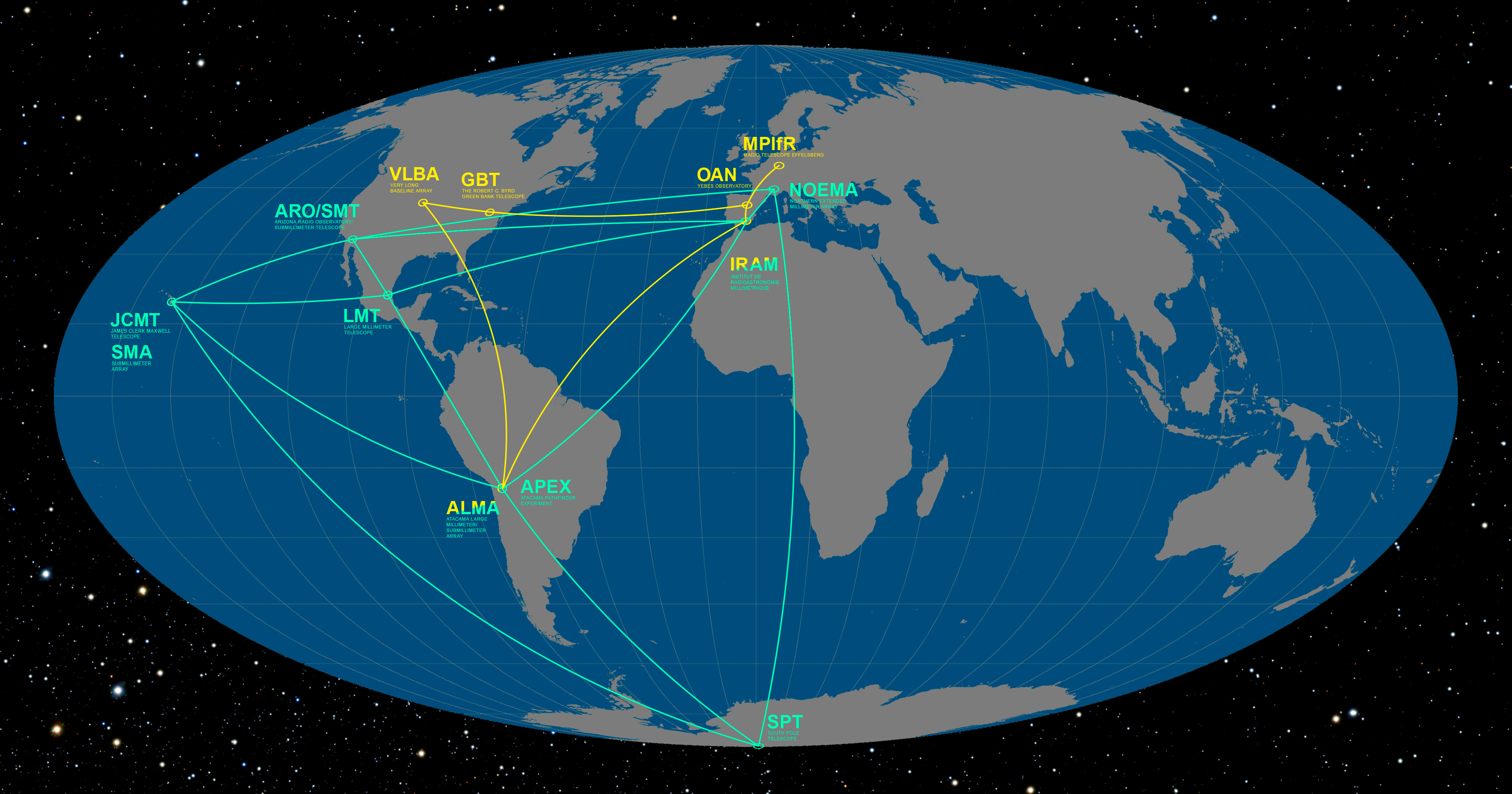

To simulate a telescope with 100 times the resolution of ALMA, telescopes must be spread over a much larger area — far beyond the Chilean Andes, beyond even South America and extending to North America and Europe. Using the Very-Long-Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) technique, telescopes of several thousand kilometers in diameter can be simulated. The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) and Global mm-VLBI Array (GMVA) both form Earth-sized telescopes that combine the observing power and the data collected by a range of telescopes across the world, including ALMA. The participating telescopes are listed below.

Please swipe right or left

| Project | Contributing Telescopes |

|---|---|

| EHT | ALMA, APEX (Chile), JCMT、SMA (Hawaii, U.S.), ARO/SMT (Arizona, U.S.), LMT(Mexico), IRAM 30m (Spain), NOEMA (France), SPT (South Pole) |

| GMVA | ALMA, VLBA (eight locations in U.S.), GBT 100m (West Virginia, U.S.), IRAM 30m (Spain), OAN 40m (Spain), Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy 100m (Germany) |

But how does VLBI work? With ALMA, it’s relatively straightforward: each antenna receives signals from a target object and then sends them via optical fibers to a central location on site, where they are processed and combined by a dedicated supercomputer. However, when telescopes are located thousands of kilometers apart — halfway across the world from each other — it’s impossible to connect them via optical fibers to a central location and transmit such enormous volumes of data. VLBI therefore uses a different technique: the data are first recorded at each individual telescope and stored on recording devices on site. These devices are then shipped or flown back to one place and played back all together in a computer for data synthesis.

A schematic diagram of the VLBI mechanism. Each antenna, spread out over vast distances, has an extremely precise atomic clock. Analogue signals collected by the antenna are converted to digital signals and stored on hard drives together with the time signals provided by the atomic clock. The hard drives are then shipped to a central location to be synchronized. An astronomical observation image is obtained by processing the data gathered from multiple locations.

Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), J.Pinto & N.Lira.

A key component of the VLBI technique are the clocks — and these are no ordinary clocks. To synthesize the data gathered simultaneously by contributing telescopes around the world, each telescope requires a clock set to the accurate time with astonishing precision. These clocks measure small differences in the arrival time of the radio waves coming from the target object to each antenna of the array. Every telescope taking part in VLBI is equipped with an extremely precise, specially-developed atomic clock — so accurate that over a period of 100 million years, each clock would be off by less than 1 second!

Hydrogen maser atomic clock installed at the ALMA Array Operations Site (AOS), along with the technicians who installed it.

Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), C. Padilla.

Another key element in VLBI is the device used to record the data. The first VLBI experiments were carried out in the 1960s and used magnetic tapes to record observations, but since entering the 21st century, more and more VLBI observations have been recorded on hard drives because of their larger storage capacity and lower prices. The hard drives used in the EHT and GMVA observations are based on magnetic-disk technology and incorporate primarily low-cost PC components.

One important aspect of such a recording device is the speed with which it records data. The faster the data recording speed, the more extensive the range of frequency signals that can be recorded, which improves the overall sensitivity of the observations. Some of the hard drives used in the EHT observations can record data at up to a total rate of 16 gigabits per second! Of course, the storage capacity of the hard drives is also important. The capacity of the hard drives ALMA used for the EHT/GMVA observations exceeds 1 petabyte (1 million gigabytes) in total.

The dedicated supercomputer to process the recorded data is called a “correlator”. The EHT correlator was developed by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the US, while the GMVA correlator was developed by the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy located in Bonn, Germany. The enormous amount of data obtained is firstly recorded at the telescopes around the world, and then sent to these two locations where it is read from each disk to the correlator at up to 4096 MB per second. The data is then processed by the correlator to form an astronomical image.

The VLBI technique can use these cutting-edge technologies to form an Earth-sized telescope capable of achieving extremely high resolution. This raises the question: Can any type of celestial object be revealed in detail by VLBI observations? Unfortunately, the answer is no. Some objects will be a good target of the VLBI observations, while others will not.

If you’ve ever used a microscope to observe a small object, you might be familiar with the experience of raising the magnification — only to see a dimmer view. The same thing happens with telescopes. Increasing the resolution means seeing an object in a view that is divided into many smaller parts. This inevitably results in decreasing the amount of light received from each part of the target object. Eventually, as the resolution increases, fainter objects become invisible.

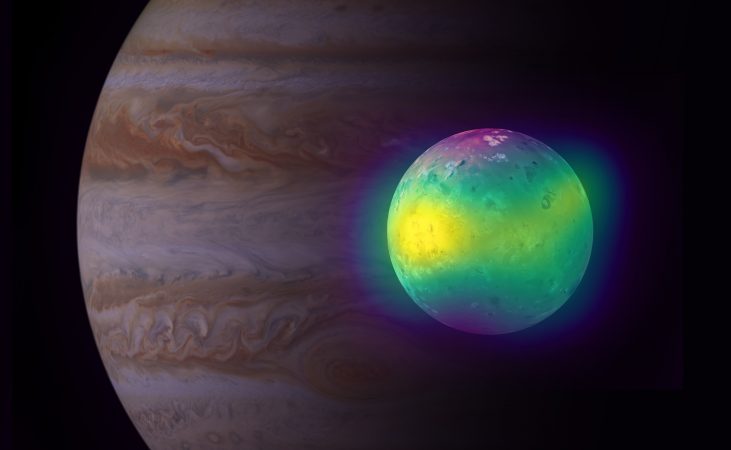

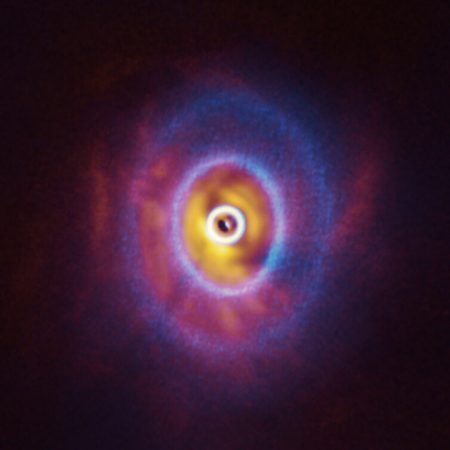

For this reason, the extraordinarily high resolution of VLBI is mainly suitable for observing bright objects. VLBI is often used to observe objects that emit intense radio waves, such as astrophysical masers (similar to the kind of lasers that we are familiar with, but at microwave wavelengths) occurring around young and old stars, and high-speed jets of gas ejected from supermassive black holes. Since a high-temperature gas disk around a supermassive black hole is thought to emit strong radio waves, the EHT and GMVA observations aim to use the VLBI technique to capture the elusive black hole at the center of the galaxy.

This is the sixth post of a blog series following the Event Horizon Telescope and the Global mm-VLBI Array projects. The next topic will focus on the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A* located at the center of the Milky Way, a high-priority target object of the EHT/GMVA observations.

![Taking the First Picture of a Black Hole [5] - How do Radio Telescopes work?](https://alma-telescope.jp/assets/uploads/2017/06/galactic_center-201706-668x340.jpg)

![Taking the First Picture of a Black Hole [4] - What’s so interesting about the event horizon?](https://alma-telescope.jp/assets/uploads/2017/05/raptor-4k-668x376.jpg)

![Taking the First Picture of a Black Hole [1] - Attempting the Impossible](https://alma-telescope.jp/assets/uploads/sites/alma.mtk.nao.ac.jp/j/news/files/editor/ann17015a-668x351.jpg)