2017.05.09

People Working for ALMA (1) Spectacular Scene Like an SF Movie: Interview with Professional Operators of Giant Transporters

This series of interviews features such people who work for the ALMA project. This first article introduces a team in charge of carrying giant antennas, a key instrument of a radio telescope, with a special vehicle called “transporter”. We interviewed with two backseat players who work behind the scenes: associate professor Norikazu Mizuno who leads the ALMA engineering group, and a local operator Juan Salamanca.

ALMA 66 Antennas Configuration Changeable at 5000 m

— ALMA is a radio telescope to observe the universe with 66 movable parabolic antennas that can be arranged to a required configuration most suitable for the reception of radio waves from a target object. How often do you move the antennas?

Mizuno: Currently, moving 10 to 20 antennas every month. Antennas are moved one by one from a compact configuration to a larger one, and then placed back to a smaller one. This process is repeated many times.

ALMA antennas extended at the Array Operations Site (AOS)

— What is the difference between the extended and compact configurations?

Mizuno: With an extended space between antennas, we can achieve higher resolution that allows us to observe details of distant objects like a zoom lens of a camera. On the other hand, with a narrowed space between antennas, we can see the extended object entirely like using a wide zoom lens. Antenna configuration can be variously arranged according to the target objects and research purposes. This is a great advantage of ALMA.

— So, antennas are arranged differently depending on each astronomer’s target of observations.

Mizuno: Actually ALMA makes announcement of the antenna configuration scheduled from October to next September every year. Astronomers around the world see the schedule and submit proposals for a period to meet the needs for their observations.

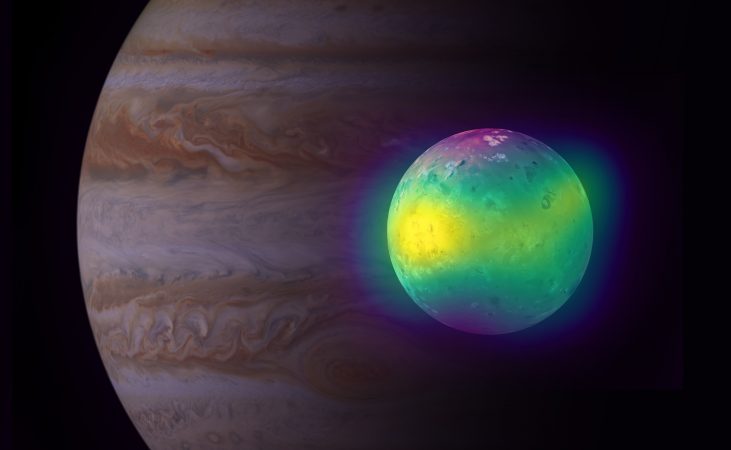

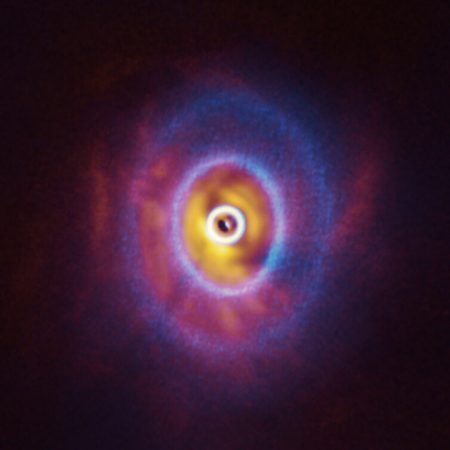

Planetary forming disk around HL Tau around 450 light years away, which was observed with an extended antenna configuration. ©ALMA (ESO / NAOJ / NRAO)

A sunspot observed with a compact antenna configuration ©ALMA (ESO / NAOJ / NRAO)

— Do you move all of 66 antennas every time?

Mizuno: Among 66 antennas, 16 Japanese antennas (four 12 m and twelve 7-m antennas) composing the Atacama Compact Array (ACA) are not necessary to be moved a lot, because they keep a very compact configuration to observe the universe with a wide field of view. A required condition for observation at this moment is that 45 antennas out of the remaining fifty 12-m antennas are set to a certain position.

When changing the configuration, we don’t move 45 antennas all together. Instead, we start with 15 antennas and gradually make a larger configuration over a week or so, and then make 3-week observations with this arrangement. And then, move another group of 15 antennas over a week to make a configuration larger than the previous one. In this way, we extend the antenna configuration bit by bit and do the same when we make a smaller configuration.

Compact configuration of 16 ACA antennas. ©ALMA (ESO / NAOJ / NRAO)

Why 100-ton Giant Antennas are Carried One by One?

— I was surprised that a 100-ton giant antenna is carried by the transporter, a vehicle with tires. How did you come up this idea?

Mizuno: In a conventional method, railroad tracks and wagons were used for antenna transportation in radio interferometers with multiple antennas like ALMA, such as the Nobeyama Millimeter Array (NMA *Ended its scientific operations), and the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA *One of the large radio telescopes operated by the U.S. National Radio Astronomy Observatory) in New Mexico.

However, unlike these telescopes, ALMA has about 200 antenna setting points. Moreover, the land is not flat enough. There are mountains and valleys along the way when we move the antennas to the most distant part. It’s not realistic at all to set railroad tracks on such a rough surface.

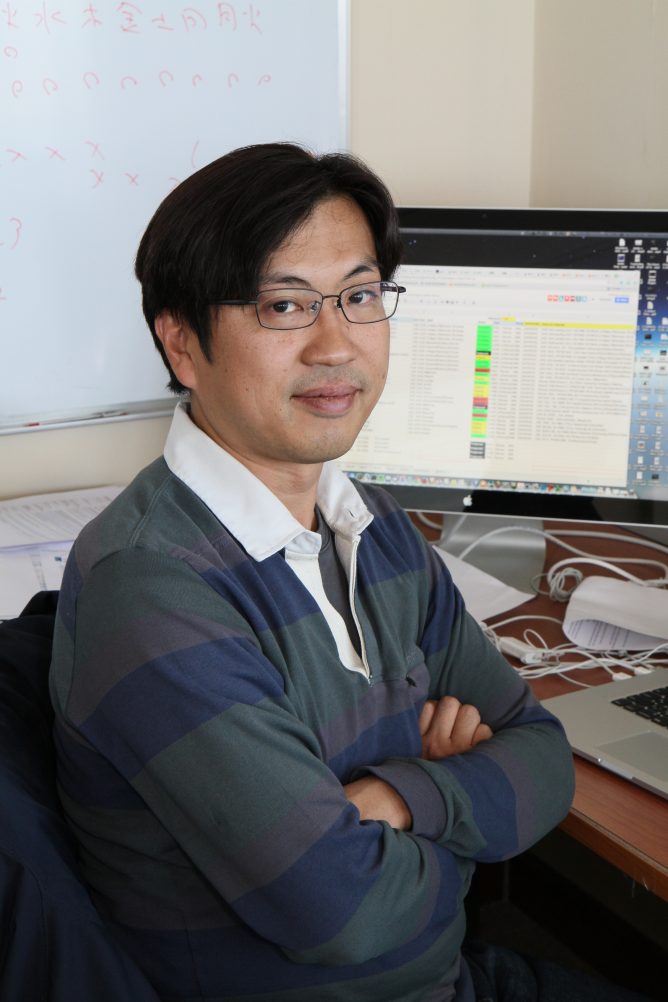

Norikazu Mizuno (Associate professor at the NAOJ Chile Observatory)

— From the aerial photo of the Atacama Desert, the areas around the Array Operations Site (AOS) look rather flat but actually there are height differences.

Mizuno: Right. And, it could be a threat to life to work with the antenna at the 5000-m high site for a long time. Then, for the maintenance of the antenna, we have to transport it down to the Operations Support Facility (OSF) at 2900m.

For such a long transportation, it could be very costly if we did it with railroads. Therefore, we decided to use a transporter with tires for antenna transportation.

Looks like a Scene of an SF Movie! Powerful Transporter 20 m Long and 10 m Wide

— Please tell me how to move the antennas in details.

Mizuno: We move the antennas in a team of 5 people. One of them is a supervisor who oversees the entire transportation work to be conducted safely and accurately. And another one will be the operator (driver) of the transporter. The remaining three are engineers to support the transportation.

Two mechanical engineers are responsible for screwing and unscrewing big bolts when loading the antenna on the transporter or on the antenna pads. The remaining one is an electrical engineer who connects and disconnects power lines and electrical signal cables.

Transporter ©ESO / Enrico Sacchetti

— How long does it take to move one antenna to a different place?

Mizuno: It takes about three to four hours. If the weather is fine, we can finish one antenna in the morning and another one in the afternoon. We have two transporters, so if we use both of them simultaneously, we can move four antennas a day, but we rarely do it. Usually we use only one of them for a day. This is because the transporter requires regular maintenance too. The staff working for the antenna transportation are also in charge of other maintenance works including mechanical maintenance of the other antennas, installation or removal of receivers, etc.

— And, the appearance of the transporter is so overwhelming! It looks like coming out of a scene of an SF movie.

Mizuno: Yes, it’s really overwhelming. That’s 6 m high, 20 m long, and 10 m wide. It has 14 tires on one side and 28 tires in total which are all independently steerable. These tires allow the vehicle to move from side to side and rotate at the same spot. And they are also driven by remote control.

Transporter moving the antenna ©ESO / S. Stanghellini

— The antenna is a heavy component of 100 tons in weight and also a high-tech precision instrument. To carry it safely, is there any special mechanism in a transporter?

Mizuno: The transporter is equipped with an individual diesel generator separate from the engine which constantly provides electricity to the antenna during transportation work. By doing this, we can keep the superconducting receivers (equipment installed into the antenna to convert collected radio waves into electrical signals) cooled at extremely low temperatures and start observations within several hours after the transportation.

Also, it has two engines so that even if one of them gets out of order during transportation, another one can bring the antenna to a safe place. Tires have similar safety measures to keep moving by lifting up a failed tire so that the uncontrollable tire won’t touch the ground. The transporter is designed to be flexible enough to be able to keep safe transportation of the antenna even in case of unexpected failure.

Transporter moving the antenna©ESO / S. Stanghellini

Collaboration with Researchers and Local Chilean Staff for Deepening Understanding of the Universe

— The operator who drives the transporter has a grave responsibility for safety. How long does it take for the training of the operator?

Mizuno: It requires special skills, but for the technical part only, it will take only two or three months. After taking paper tests and safety training programs including the detection of abnormalities during operations, some quick learners can start driving the transporter with a “provisional license” within 6 months. Becoming a full-fledged operator would require one year.

— How many operators do you have and how do they work in shifts?

Mizuno: Currently, we have four Chilean operators. Since working at high sites could be physically very strenuous, they work for 8 days and take 6 days off. ALMA is not a project only for astronomers, but also has another aspect of collaboration with local Chilean people where we work together to deepen mutual understandings and increase awareness of the universe and astronomical observations.

Operator driving the transporter ©ESO / Max Alexander

— Are there many operators who have personal interest or knowledge of astronomy?

Mizuno: More people get interested in astronomy after they started working. In the morning meeting, we show observation images taken with an extended antenna configuration and a compact one, saying “we successfully obtained great results like this, thanks to you”, so that operators can share the same feeling and become much more motivated.

On one occasion, when we had a delay on the scheduled antenna configuration due to consecutive days of bad weather, an operator made a suggestion to move two antennas for the day despite an original plan to move one antenna only. Thanks to their proposal, we made up for the delay and could start a new observation from the next day. We were so happy about it and they looked so proud of their work.

However, there are physical risks and strains in the work at high altitudes of 5000 meters, which may cause careless human errors like forgetting to tighten screws. Keeping this in mind, we pay great attention to the balance of the workload and safety as one of our important jobs.

Proud of Engineering Team Working at 5000-m High Site

— ALMA’s capability can be fully achieved with the support of operators and engineering staff who transport giant antennas.

Mizuno: Exactly. We have an annual plan to transport antennas 150 times for this season, but probably we have to do it 200 times a year for the next season. There are an increasing number of requests from astronomers wishing to make observations with ALMA, which resulted in the over-subscription rate of four for this season.

In order to make various observations in response to increasing requests, we need an increased number of antenna transportation. However, it means we have to keep moving antennas almost every day except for bad weather days. It could be very hard work, but we are now discussing if it is realistic or not.

Transporter moving the antenna ©Enrico Sacchetti / ESO

— I suppose the transporter is very robust, but is it durable enough to keep carrying 100-ton antennas almost every day?

Mizuno: Among the subsystems of ALMA, some components are constantly upgraded and designed to be easily replaced; for example, the superconducting receivers (instruments to receiver weak radio waves) installed inside the antenna and the correlator (supercomputer) to make an image by combining radio waves received by multiple antennas.

However, the antenna itself and the transporter will be used at least for 30 years. How we maintain properly these two key components of ALMA will determine the future of the observatory.

We, all engineering staff, are working with such awareness and proud as a person responsible for the maintenance of ALMA. We would be happy if many people could understand it and support us.

Interview with Local Transporter Operator

Lastly, we asked some questions to a Chilean operator Juan Salamanca and got answers from him by e-mail. We are pleased to present here the interview with him as follows:

— What brought you to the ALMA project?

Salamanca: I was working in the Chilean Navy Air Corps and served as an electronic technician and engineer for control and instrumentation over 20 years. Taking advantage of such skills and experiences, I got a job at ALMA eight years ago and have been working as a transporter operator for six years.

— What kind of training did you take to become an operator?

Salamanca: I had lectures and practical training by the company Scheuerle, a developer of the transporter at the Operations Support Facility (OSF). In addition to these, I learnt about electrical systems, electronic components, hydraulic systems, and machinery through operation practices and maintenance works.

A Chilean transporter operator Juan Salamanca

— What is the most difficult part of operating the transporter?

Salamanca: At the 5000-m high site, the most formidable enemy is a severe natural environment such as strong wind, strong sunshine and ultraviolet radiation, thin and dry air, etc. Especially, working under a low-oxygen environment causes a decline of cognitive ability and physical performance.

And, another risk is a gradual deterioration of metal components of the transporter, which is caused by exposure to the outside air. Keeping this in mind, I do my work carefully with attention to basic things such as proper functions of all systems to carry the 100-ton antenna safely.

— I guess you are doing very hard work. What do you think is the most challenging part of your work?

Salamanca: I find it very challenging and exciting to drive the transporter and carry the antenna, to implement the system maintenance thoroughly, and to find room for improvement and make adjustments for it.

Needless to say, it’s also challenging for me to work as a member of the world’s largest observatory that makes extraordinary discoveries. I hope maintaining these two custom-built transporters properly will make it possible to continue ALMA observations on the land of Atacama for 25 years, 35 years, or for a longer period of time.