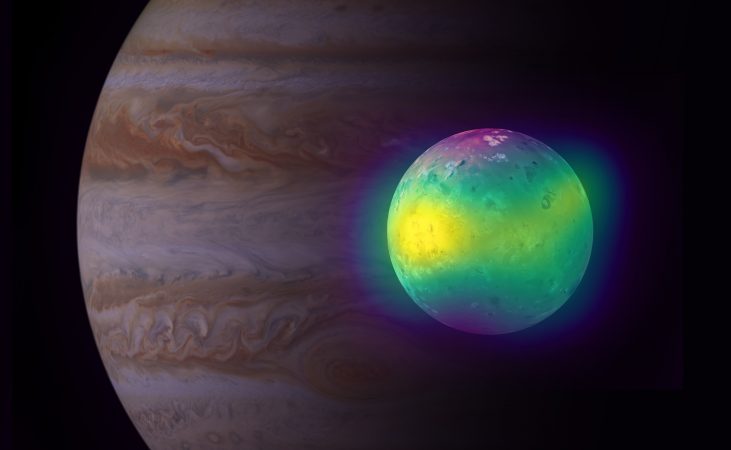

Jupiter’s icy moon Europa has a chaotic surface terrain that is fractured and cracked, suggesting a long-standing history of geologic activity.

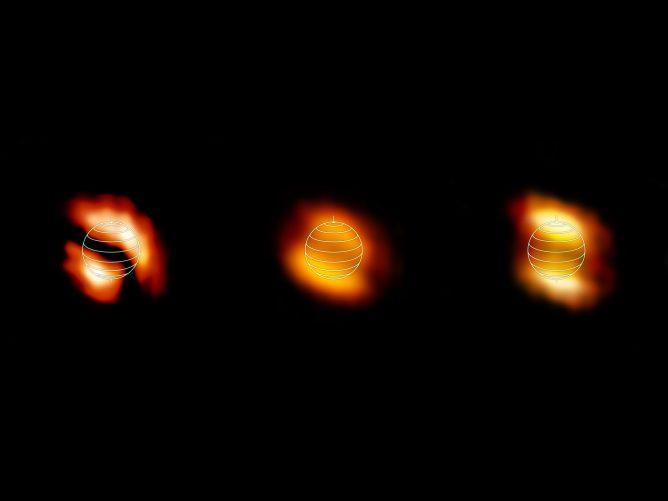

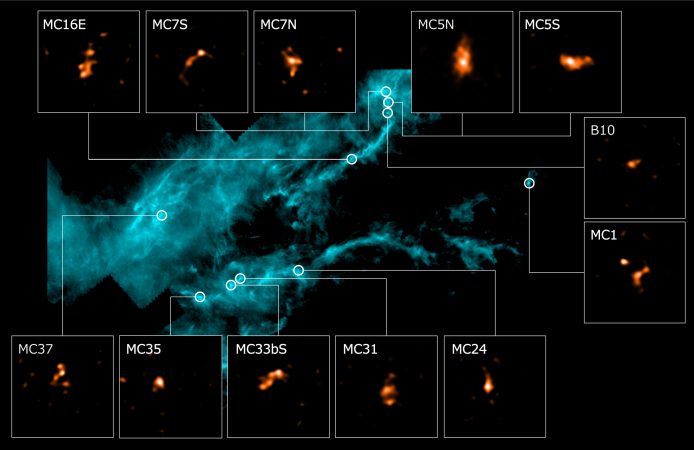

A new series of four images of Europa taken with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) has helped astronomers create the first global thermal map of this cold satellite of Jupiter. The new images have a resolution of roughly 200 kilometers, sufficient to study the relationship between surface thermal variations and the moon’s major geologic features.

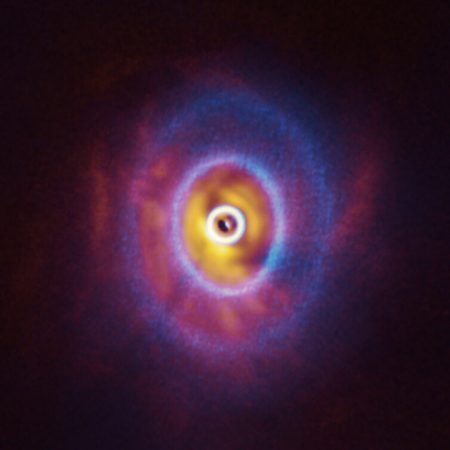

ALMA image of Jupiter’s moon Europa. ALMA was able to map out thermal variations on its surface. Hubble image of Jupiter in the background.

Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), S. Trumbo et al.; NRAO/AUI NSF, S. Dagnello; NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope

The researchers compared the new ALMA observations of Europa to a thermal model based on observations from the Galileo spacecraft. This comparison allowed them to analyze the temperature changes in the data and construct the first-ever global map of Europa’s thermal characteristics. The new data also revealed an enigmatic cold spot on Europa’s northern hemisphere.

“These ALMA images are really interesting because they provide the first global map of Europa’s thermal emission,” said Samantha Trumbo, a planetary scientist at the California Institute of Technology and lead author on a paper published in the Astronomical Journal. “Since Europa is an ocean world with potential geologic activity, its surface temperatures are of great interest because they may constrain the locations and extents of any such activity.”

Series of 4 images of the surface of Europa taken with ALMA, enabling astronomers to create the first global thermal map of Jupiter’s icy moon.

Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), S. Trumbo et al.

Evidence strongly suggests that beneath its thin veneer of ice, Europa has an ocean of briny water in contact with a rocky core. Europa also has a comparatively young surface, only about 20 to 180 million years old, indicating that there are as-yet-unidentified thermal or geologic processes at work.

Unlike optical telescopes, which can only detect sunlight reflected by planetary bodies, radio and millimeter-wave telescopes like ALMA can detect the thermal “glow” naturally emitted by even relatively cold object in our Solar System, including comets, asteroids, and moons. At its warmest, Europa’s surface temperature never rises above minus 160 degrees Celsius (minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit).

“Studying Europa’s thermal properties provides a unique means of understanding its surface,” said Bryan Butler, an astronomer at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Socorro, New Mexico, and coauthor on the paper.

Paper and the research team

These observation results were published as Trumbo et al. “ALMA Thermal Observations of Europa” in the Astronomical Journal on September 2018.

The research team members are:

Samantha K. Trumbo (California Institute of Technology), Michael E. Brown (California Institute of Technology), Bryan J. Butler (National Radio Astronomy Observatory)