Peering deep into space — 90 percent of the way across the observable universe — astronomers have witnessed the beginnings of a gargantuan cosmic pileup, the impending collision of 14 young, starbursting galaxies. This ancient megamerger is destined to evolve into one of the most massive structures in the known universe: a cluster of galaxies, gravitationally bound by dark matter and swimming in a sea of hot, ionized gas.

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an international team of scientists has uncovered a startlingly dense concentration of 14 galaxies that are poised to merge, forming the core of what will eventually become a colossal galaxy cluster.

This tightly bound galactic smashup, known as a protocluster, is located approximately 12.4 billion light-years away, meaning its light started traveling to us when the universe was only 1.4 billion years old, or about a tenth of its present age. Its individual galaxies are forming stars as much as 1,000 times faster than our home galaxy and are crammed inside a region of space only about a quarter the size of the Milky Way. The resulting galaxy cluster will eventually rival some the most massive clusters we see in the universe today.

The results are published in the journal Nature.

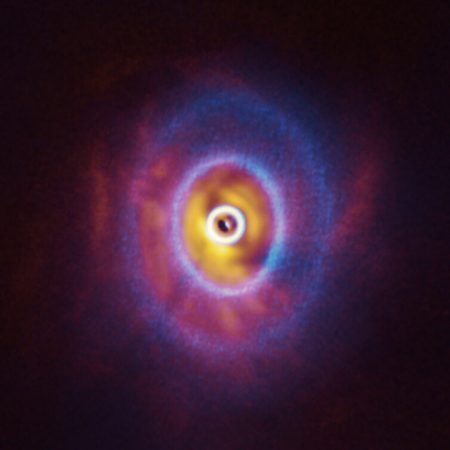

This artist’s impression of SPT2349-56 shows a group of interacting and merging galaxies in the early Universe. Such mergers have been spotted using the ALMA and APEX telescopes and represent the formation of galaxies clusters, the most massive objects in the modern Universe. Astronomers thought that these events occurred around three billion years after the Big Bang, so they were surprised when the new observations revealed them happening when the Universe was only half that age.

Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser

“Having caught a massive galaxy cluster in throes of formation is spectacular in and of itself,” says Scott Chapman, an astrophysicist at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada, who specializes in observational cosmology and studies the origins of structure in the universe and the evolution of galaxies.

“But, the fact that this is happening so early in the history of the universe poses a formidable challenge to our present-day understanding of the way structures form in the universe,” he said.

During the first few million years of cosmic history, normal matter and dark matter began to aggregate into larger and larger concentrations, eventually giving rise to galaxy clusters, the largest objects in the known Universe. With masses comparable to a million billion suns, clusters may contain as many as a thousand galaxies, vast amounts of dark matter, gargantuan black holes, and X-ray emitting gas that reaches temperatures of over a million degrees.

Current theory and computer models suggest that protoclusters as massive as the one observed by ALMA, however, should have taken much longer to evolve.

“How this assembly of galaxies got so big so fast is a bit of a mystery, it wasn’t built up gradually over billions of years, as astronomers might expect,” said Tim Miller, a doctoral candidate at Yale University and coauthor on the paper. “This discovery provides an incredible opportunity to study how galaxy clusters and their massive galaxies came together in these extreme environments.”

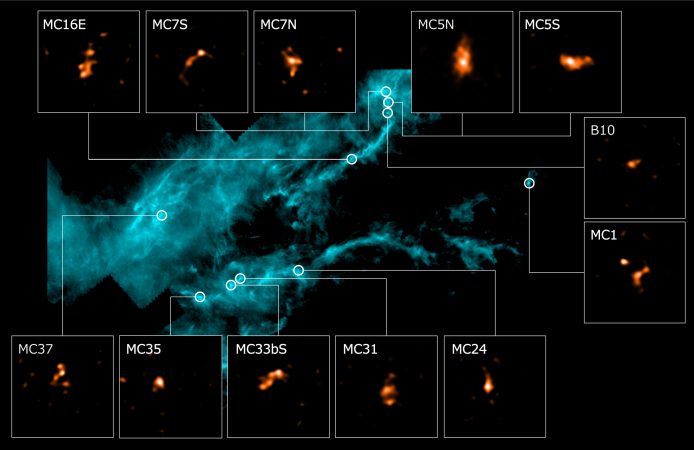

This particular galactic protocluster, designated SPT2349-56, was first observed as a faint smudge of millimeter-wavelength light in 2010 with the National Science Foundation’s South Pole Telescope. Follow-up observations with the Atacama Pathfinder Experiment (APEX) telescope helped confirm that it was in fact an extremely distant galactic source and worthy of follow-up observations with ALMA. ALMA’s superior resolution and sensitivity allowed astronomers to distinguish no fewer than 14 individual objects in a shockingly small region of space, confirming the object was the archetypical example of a protocluster in a very early stage of development.

This montage shows three views of the distant group of interacting and merging galaxies called SPT2349-56. The left image is a wide view from the South Pole Telescope that reveals just a bright spot. The central view is from Atacama Pathfinder Experiment (APEX) that reveals more details. The right picture is from ALMA and reveals that the object is actually a group of 14 merging galaxies in the process of forming a galaxy cluster.

Credit: ESO/ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/Miller et al

This cluster’s extreme distance and clearly defined components offer astronomers an unprecedented opportunity to study some of the first steps of cluster formation less than 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang. By using the ALMA data as the starting conditions for sophisticated computer simulations, the researchers were able to demonstrate how this current collection of galaxies will likely grow and evolve over billions of years.

“ALMA gave us, for the first time, a clear starting point to predict the evolution of a galaxy cluster. Over time, the 14 galaxies we observed will stop forming stars and will collide and coalesce into a single gigantic galaxy,” says Chapman.

The National Radio Astronomy Observatory is a facility of the National Science Foundation, operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.

Paper and the research team

This research is presented in a paper titled “A massive galaxy cluster core at a redshift of 4.3,” by T.B. Biller, et al., which appears in the journal Nature.

The research team members are:

T. B. Miller (Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada; Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA), S. C. Chapman (Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada; Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge, UK), M. Aravena (Universidad Diego Portales, Santiago, Chile), M. L. N. Ashby (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA), C. C. Hayward (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA; Center for Computational Astrophysics, Flatiron Institute, New York, New York, USA), J. D. Vieira (University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois, USA), A. Weiß (Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie, Bonn, Germany), A. Babul (University of Victoria, Victoria, Canada) , M. Béthermin (Aix-Marseille Université, CNRS, LAM, Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille, Marseille, France), C. M. Bradford (California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California, USA; Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California, USA), M. Brodwin (University of Missouri, Kansas City, Missouri, USA), J. E. Carlstrom (University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois USA), Chian-Chou Chen (ESO, Garching, Germany), D. J. M. Cunningham (Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada; Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada), C. De Breuck (ESO, Garching, Germany), A. H. Gonzalez (University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA), T. R. Greve (University College London, Gower Street, London, UK), Y. Hezaveh (Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA), K. Lacaille (Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada; McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada), K. C. Litke (Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, USA), J. Ma (University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA), M. Malkan (University of California, Los Angeles, California, USA) , D. P. Marrone (Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, USA), W. Morningstar (Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA), E. J. Murphy (National Radio Astronomy Observatory, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA), D. Narayanan (University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA), E. Pass (Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada), University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Canada), R. Perry (Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada), K. A. Phadke (University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois, USA), K. M. Rotermund (Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada), J. Simpson (University of Edinburgh, Royal Observatory, Blackford Hill, Edinburgh; Durham University, Durham, UK), J. S. Spilker (Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, USA), J. Sreevani (University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois, USA), A. A. Stark (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA), M. L. Strandet (Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie, Bonn, Germany) and A. L. Strom (Observatories of The Carnegie Institution for Science, Pasadena, California, USA).