2020.11.11

People Working for ALMA (4) Interview with a Front-Line Astronomer Working in the ALMA Control Room

Physically hard work in remote highlands

── We are glad to have you here. In today’s interview, we would like to hear about the work of astronomers at the OSF.

Takahashi: Thank you for having me. I am working as a member of the ALMA Department of Science Operations (DSO) at the Joint ALMA Observatory (JAO). Our department consists of a wide variety of people such as researchers like me in the field of astronomy, telescope operators, and specialists who have technical backgrounds. At the OSF, each member of the DSO has different responsibilities in the telescope operations. I would like to share with you how we are working there.

Satoko Takahashi (NAOJ Chile) having the interview at the west-facing terrace of the OSF.

Credit: NAOJ

── Let’s start from a basic question. Are you usually staying at the OSF?

Takahashi: No, we, the members of the DSO, are working in shifts at the OSF. I usually spend most of my working hours at the JAO office in Santiago. I come to the OSF for on-site observation operations about eight times a year and one visit spans eight days.

It takes two hours by airplane from Santiago to the local airport and another two hours to get to the OSF from the airport by observatory’s shuttle bus. Although it is a domestic travel in Chile, it must be hard to travel such a long distance frequently.

Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)

Takahashi: The frequency of shifts varies according to job types and assigned workload. I have a colleague in the DSO who visits the OSF as many as 14 times a year. Colleagues from the engineering department and telescope operators, who are based at OSF, come to the OSF every other weeks.

── Oh, it must be very hard.

Takahashi: The work here is physically tough and requires physical strength.

── The OSF is located at 2,900-m altitude. It is an equivalent level to the seventh to eighth station of Mt. Fuji. Have you ever suffered from altitude sickness?

Takahashi: I heard that the susceptibility to altitude sickness depends greatly on inherent predisposition. I have no problem at 2,900 m.

── Before going into the details of your work in the DSO, could you explain how ALMA observations are carried out and the reason why the members of the DSO need to be stationed at the OSF?

Takahashi: ALMA is a telescope open to all astronomers around the world. They do not have to come to the observation site and operate the telescope by themselves. ALMA is operated based on a method called “dynamic scheduling” in which the order of observations is changed flexibly according to the situation at the time of observation. We the members of the DSO decide the observation schedule and carry out the observations from the control room on behalf of astronomers around the world.

Operating 66 antennas remotely with several people

── We are here in the control room that you were talking about.

── Are you sitting here when you are conducting actual observations?

Takahashi: Yes. We work in three shifts around the clock here. When I’m on duty, I sit in front of this display.

── There are many displays here.

Takahashi: I will explain how we use them. For example, this display shows the amount of water vapor and atmospheric fluctuations. While looking at it, we check the weather conditions and decide how high-frequency we can observe. When the amount of water vapor increases, it becomes more difficult to conduct high-frequency (i.e., short wavelength) observations.

We can see some graphs of the current weather conditions on the right side of the display. The graph at the top shows the time variations of the Precipitable Water Vaper (PWV). The PWV is expressed by the height in millimeters and represents the total amount of liquid water that could be precipitated as a result of condensation of all atmospheric water vapor contained in a vertical column (from the earth’s surface to the uppermost layer of the atmosphere) of a given area. When this photo was taken, the PWV was 1.76 mm but it could be lower than 0.5 mm in the best condition. It happens several times a year. Since higher-frequency radio waves are more susceptible to water vapor absorption, we need to find the right time when the PWV is sufficiently low in order to carry out the ALMA observation at the highest possible frequency. The second top graph on the screen shows the atmospheric fluctuations.

Credit: NAOJ

Takahashi: We have another display here. We use this display to see a list of observation projects that could be carried out under the current weather conditions. ALMA observations are implemented based on observation proposals submitted by researchers. To have their observations carried out, they need to go through a proposal review of their projects. What we are seeing now is the list of the projects accepted for this Cycle. We carry out each observation considering various factors such as the priority given by the proposal review committee, required angular resolution, locations of celestial objects at the time of observation, weather conditions, and so on. Regional balance is also an important factor in implementing observations. Since ALMA is a global partnership of East Asia, Europe, and North America, the observation time is allocated to each region in proportion to the share of contributions. We have to avoid any inequitable conduct like only carrying out many projects from one region. The priorities are set so as to ensure a proper regional balance.

Takahashi: We astronomers on duty carry out observations from the one that has higher priority according to the conditions. When we need to change any part of the observation plans, we consult with telescope operators. They do the initial settings of the telescope and check closely the status of each antenna.

Takahashi: On this display, we use the software to implement observations. By selecting an observation file and executing it, we can run the observations and monitor the status of observation on another display. We check whether the telescope is working properly and the observation is being carried out at appropriate observing frequencies on the monitor. If we find any irregularities in the values on the screen, we will investigate the problem together with telescope operators.

A set of four displays that astronomers use in the control room. While checking the information on these screens, astronomers conduct observations.

Credit: NAOJ

Takahashi: We also have a display to see the observation results. During observations, we are monitoring the data on an almost real-time basis to check for any abnormalities in the operations. After an observation finishes, a quick data processing software is automatically activated and we can obtain an image in about one hour. We check closely the result for quality assurance of the observation data.

── Are you looking at the screens like this all the time during actual observations?

Takahashi: Yes. We are seeing whether the instruments are working well and all the antennas are receiving signals properly while checking the weather information. To reduce the downtime between observations, it is also important to make preparations for the next observation. Along with these tasks, we have to check the data for quality assurance.

── You have a lot of things to do. It must be hard work.

Takahashi: Yes, we’re very busy. If we do not have any problem, we can complete the assigned tasks in the procedure as explained earlier. However, if anything unexpected occurs, it could halt the observation. For example, if a failure is found in one antenna, we have to decide whether to take time for recovering the antenna, or separate the failed antenna from the system and resume the observation with the remaining antennas. We don’t want to waste any minutes of the valuable ALMA observation time. While the telescope operators and engineers investigate the actual cause of the trouble and fix it, we astronomers in the DSO make judgements on how to deal with the situation. Since ALMA consists of complicated systems, no one can solve a problem completely by oneself. The solution is to divide the work. We often ask engineers to fix the troubles, specifying the priorities and the deadline like “please fix this before tonight’s observation.” I am grateful to these technical specialists for keeping all antennas working properly and functioning as part of the entire telescope system for everyday operations.

── Your work may be very hectic, but the control room is apparently rather quiet.

Takahashi: It might look that way. Usually four to six people are here on duty at all times in every shift, which include two telescope operators and two staff who have astronomical backgrounds. As it is important for us to concentrate on the tasks, we try to minimize the number of people working here so as to conduct the work efficiently.

── You have no time to enjoy looking at the actual observation data, I guess.

Takahashi: We concentrate on our mission of keeping the telescope working properly and obtaining high-quality observation data. In ALMA observations, we need to observe calibration sources, in addition to the target objects. A potential calibrator is a quasar, which is a core of a very distant galaxy and point-like source in the sky. Radio waves emitted by quasars go through Earth’s atmosphere and various telescope systems before detection. So, we need to measure and calibrate those influences. We can use a calibration source to monitor fluctuations that are attributed to instruments and atmosphere. If calibrator sources are not clearly observed, we are not able to process the data for research use. One of the most important tasks is to check in real time whether the calibration source is being observed with no fail. During observations, we also watch carefully the status of each antenna. Imagine a situation where an observation was conducted with 45 antennas, but we found out later that three antennas were not working. If that happens, we cannot deliver the observation data in a complete form. So, we monitor and check if the data is being taken as required by the proposer. Delivering quality-assured data to astronomers is an important mission in ALMA.

A sign that urges people to be quiet at the OSF accommodation facility. Since ALMA is operated around the clock, some staff members are sleeping during the day. The mountain in the back is Licancabur Volcano (5,916 m above sea level) which straddles the border between Chile and Bolivia. The volcano is a symbol of the area around the ALMA observatory. It looks similar to Mt. Fuji in Japan.

Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)

Meetings, E-mails, and Astronomer on Duty. Life at the OSF

── Could you tell us about your daily schedule at the OSF?”

Takahashi: We have different tasks in each shift. I have been undertaking a role to coordinate astronomers on duty tasks. The task includes attending three meetings a day, at 8:15 a.m., 3 p.m. and 5 p.m. The morning meeting is held among colleagues from the engineering department and DSO. We review what occurred in the previous night, and decide who will respond to the problems and how we can fix them during the daytime maintenance. In the DSO meeting at 3:00 p.m., we summarize the observations of the previous day, including what kind of system troubles we had and how much of those are recovered, and discuss how to carry out the observations at night. At 5:00 p.m., we meet again with the same members of the morning meeting and check the progress of the work to resolve the problems, and make a final check on how many antennas are available for the observation on that night.

── I see.

Takahashi: As a supervisor and coordinator of astronomers on duty in this shift, I need to attend three meetings during work hours from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. I prepare a report about the current status of the telescope and the schedule for that night and ask the person on the night shift to take care of the rest of the work. The group of astronomers on duty consists of one coordinator, one in charge of the morning shift, one in the daytime shift, and two in the night shift. While sometimes we conduct various observations 24 hours in a row, in other days observations only start from the evening after the day-time maintenance.

Takahashi: Moreover, I make arrangements for high-priority observations and observations to be implemented at a designated time, along with checks and adjustments of repaired antennas so as to make them operational in scientific observations as soon as possible. I am exchanging email messages and making coordination with the technical coordinators from the engineering department all day long. Throughout such a long hour shift, we coordinators need to keep concentration and make instant decisions all the time. We continue it for eight consecutive days. I feel exhausted at the end of the shift.

── Do you have a chance to go to the Array Operations Site at 5,000 meters where the antennas are located?

Takahashi: Technical staff go up to the array site several times in a shift, but we the DSO members rarely go up to the 5,000-m altitude on duty. Once a year, I accompany students’ visit to the AOS. I spend most of the time in the control room without looking at the telescope. I sometimes feel a lack of a sense of reality.

── I can imagine that.

Takahashi: Actually, I had such feeling today. My colleague was carrying out the observation that I proposed, but I couldn’t get a real sense of my observation being performed (laugh). In my previous work before ALMA, I could directly see the telescope moving in front of me and observations going on. But we are not able to do it with ALMA since the antennas are at 5,000-m altitude. It feels a little strange.

── Do you have other tasks in addition to carrying out observations?

Takahashi: Along with the daily science operations for the researchers from all over the world, we have another important task of conducting test observations for the future observation cycles. A certain amount of the ALMA science operation time is allocated for the test purpose, hence we also perform the test observations. ALMA is upgraded with new observing modes and capabilities on a constant basis. In order to make these new functions available to researchers around the world, we need to conduct tests to verify the new observing modes and capabilities. Examples of such efforts includes: implement new observing method for the high-frequencies to improve the calibration accuracy and new observing scheme to significantly increase the observing efficiency. We sometimes face new challenges that no one has ever experienced before even at other observatories.

── All those tasks must require the on-site involvement of a person who has astronomical backgrounds, I guess.

Takahashi: At the initial phase, we needed a person who has specialized knowledge since we were doing all works manually. Now the situation is different. We need more cooperation among co-workers to understand the entire system. As each system is more automated than before, we place higher value on teamwork that helps people work together in accordance with procedures.

── I can imagine team work would be essential when diverse people work together in a closed space like the OSF. How is the life at the OSF?

Takahashi: I am now staying at a new accommodation facility that was opened last year in the OSF. We feel very comfortable here since we were staying until only recently at a temporary lodging facility. We are also happy about the food at the OSF as it is getting better every year.

── How do you spend your free time at the OSF?

Takahashi: We spend our free time in various ways, like doing workouts in a gym and swimming pool in the annex to the accommodation facility, playing musical instruments in a band formed among staff members, playing billiards and more. When we have students’ visit to the OSF, we occasionally hold a star party outside with a telescope. I have no particular activity to join regularly, but I feel as if I am participating in a training camp during the shift at the OSF to complete the assigned tasks.

ALMA Operations Support Facility at 2,900 m altitude is a 30 minute-drive from the nearest town San Pedro de Atacama. The building shown at the center of the photo is the Technical Building that has the antenna control room and laboratories. Accommodations are located in front of this building (not shown in the photo).

Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)

Making a Best Team in Collaboration with Coworkers around the World

── Could you tell us about the best things and difficulties in working in an international project?

Takahashi: Maybe, the best part is working on site. The ALMA project is operated by the JAO, where I am working now, and by the Regional ALMA Support Centers in East Asia, North America, Europe. While the JAO assumes the operations of the ALMA site in Chile, the Regional ALMA Support Centers serve as a contact to provide support for respective regional ALMA user communities. Personally, I am more interested in on-site work because we can see the observation data in real time. While we are here, we often face various challenges but we can solve them with our own ideas. Also, we can carry out tests and verifications on site. I enjoy working here since I can feel it more real that we are making direct contributions to daily observations.

Takahashi: One of my tasks is to search for calibration sources and conduct preliminary checks before actual observations. I started from making a plan and building a team while no one knows what approach could be effective. We coordinate with experts at each regional center as needed. I also enjoy having various opportunities to work with a variety of people.

── It seems you are working with a wide range of people, indeed.

Takahashi: Yes, we are. In the ALMA operations, it is essential to coordinate with specialists who are scattered all over the world beyond the boundaries of teams or fields of expertise in order to attain the ideal telescope operations. I think I am having valuable experiences while putting heads together and solving problems that cannot be tackled by myself in collaboration with my colleagues.

── What is the difficult part?

Takahashi: Too many business trips! In addition to the trips to the OSF, we astronomers have many occasions to attend workshops and visit collaborators overseas. I travel almost every month. So, it’s difficult to have a relaxed time at home or have a time to sit down and address one thing even at my office in Santiago.

Takahashi: People of various nationalities are working at the observatory based on different employment conditions. Their views about work are quite different. One of the differences is seen in the working hours between people working in a specified work hours and people who work in a discretionary work system. Another difference is in work attitudes, whether it’s for the success of a project, family, vacations, or many other things.

── That is a “cultural difference” literally.

Takahashi: Another difficult thing is that we have to deal with many issues promptly. If any trouble occurs during observations, we have to solve the problem by the end of the day. Also, in many occasions, things do not proceed as planned even if we make a long-term plan. While dealing with such unexpected issues, we have to make a time for conducting our own research. I find it challenging in a good way but also difficult in terms of time management. In my position, I am required to produce research results while engaging in operations at the observatory. There are no clear criteria on how to evaluate my performance. I had never worked in work environment like this and neither had my boss. So, we are all striving to find a good way through a trial and error process.

Focusing on observational study of newborn stars with ALMA

── Last but not least, could you explain your research activities?

Takahashi: My focus is to reveal the formation process of stars like the Sun. In particular, I am working on the research theme of searching for young stars under 10,000 years of age and studying their properties by observations.

── Did the advent of ALMA have much impact on your research?

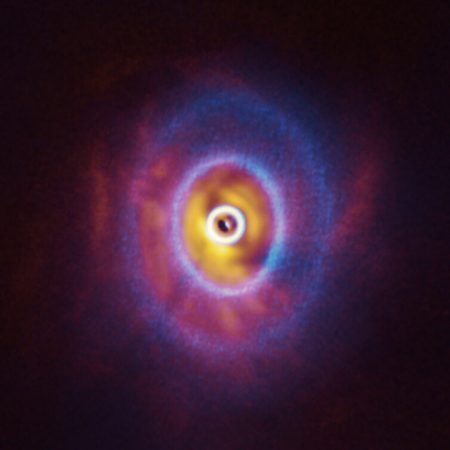

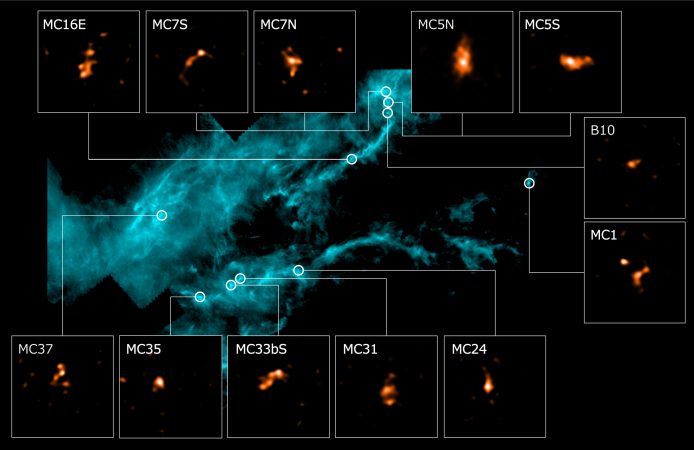

Takahashi: It was a big impact on my research. The biggest change is a significant improvement in spatial resolution and sensitivity. The resolution of the data I recently obtained was 0.02 arcsec, which is a resolution equivalent to 3000 times better than a normal visual acuity of humans. At this level of resolution, we can see the distribution of dust and gas around a newborn star more clearly than ever before, and we can also see the structures within 10 au from the star (au stands for astronomical unit: one au is equivalent to the distance between the Earth and the Sun, which is approximately 150 million kilometers. Saturn’s orbital radius is about 10 au). Lately, I have been studying magnetic field structures in the neighborhoods of protostars by tracing the polarization of radio waves. Furthermore, I began a comparative study using observation results and simulations with models.

── Was it difficult to make a comparative study with simulations in the past?

Takahashi: I had never thought of doing it (laugh). Some intricate spiral-like structures around baby stars that were only seen in simulations are becoming observable in actual observations with ALMA. Then, it enabled us to make a direct comparison. We have now a rich pool of observation data, but it is getting more difficult to put them together in papers. We have been conducting data analyses and discussions with graduate students in Japan as well as with undergraduates who come to Chile as summer students for on-site training.

── Thank you very much for taking the time for this interview. We are looking forward to your future success.

Takahashi: Thank you.