2025.12.10

Observations of the Small Magellanic Cloud: Insights into Star Formation in Early-Universe-like Environments

This article is based on the press release from Kyushu University on February 20, 2025 (https://www.kyushu-u.ac.jp/en/researches/view/325).

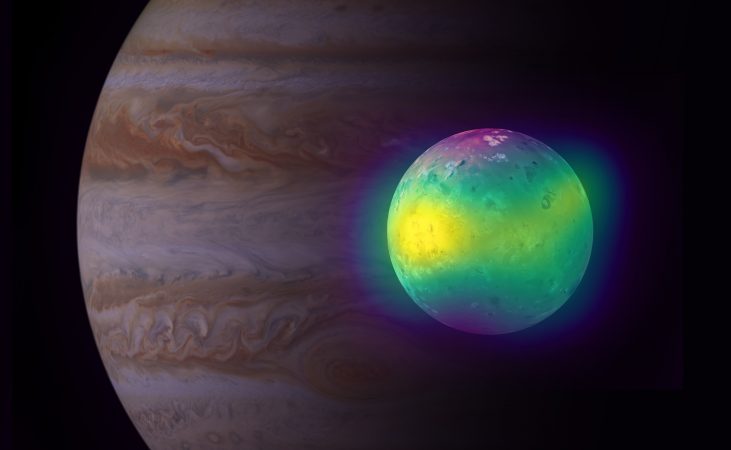

The Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC), a dwarf galaxy near the Milky Way, contains only about one-fifth the abundance of heavy elements found in our galaxy. This low abundance makes the SMC a close analog to the environments of the early Universe, roughly 10 billion years ago. Located about 200,000 light-years from Earth, it offers a rare opportunity to examine the primeval star-formation process in detail.

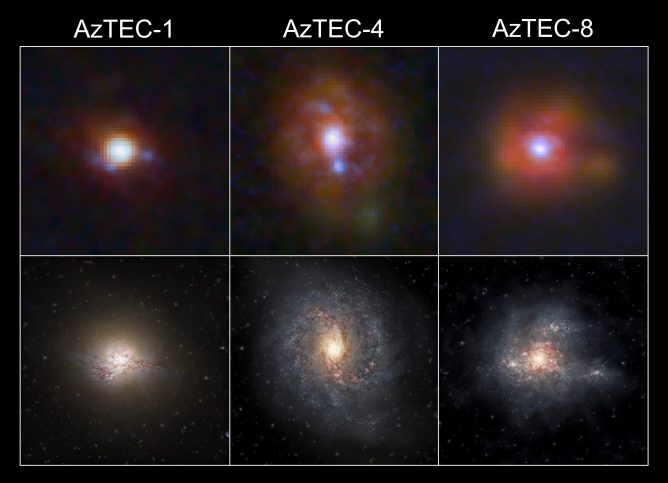

In star-forming regions of the Milky Way, molecular clouds typically exhibit elongated, “filamentary” structures approximately 0.3 light-years wide. Large filamentary clouds fragment into smaller regions known as molecular cloud cores—sometimes called “stellar eggs”—which eventually collapse to form stars.However, whether similar filamentary structures exist in the SMC has remained uncertain, largely due to the limited spatial resolution of previous observations.

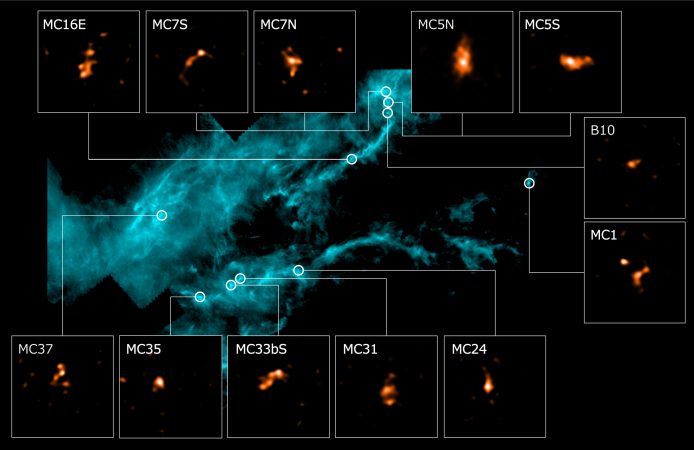

A research team led by Kazuki Tokuda, a Postdoctoral Fellow at Kyushu University’s Faculty of Science and ALMA Project, NAOJ (currently a Lecturer at Kagawa University), in collaboration with Osaka Metropolitan University, analyzed data from 17 molecular clouds in the SMC, which host growing “baby stars” (protostars) up to 20 times the mass of our Sun. Using ALMA, which provides the high-resolution radio imaging required for such studies, the team found that about 60% of the observed molecular clouds exhibit filamentary structures, while the remaining 40% display a more “fluffy” morphology. Moreover, the temperature inside the filamentary clouds was higher than that of the fluffy clouds.

Initially, molecular clouds are heated through collisions with one another. In environments rich in heavy elements, such as the Milky Way, these clouds cool rapidly by radiating energy. However, clouds with very few heavy elements take longer to cool and therefore remain at higher temperatures. When the temperature is high, turbulence within the molecular cloud is relatively weak. As the cloud cools, the kinetic energy of infalling gas drives turbulence that disrupts the filamentary structure, producing a more “fluffy” morphology. This difference between filamentary and fluffy clouds likely reflects how long the cloud has been evolving, and the shape may continue to change during the star-formation process.

If a molecular cloud retains its filamentary shape, it is more likely to fragment along its elongated “string” and form numerous low-mass stars hosting planetary systems, like our Sun. Conversely, if the filamentary structure cannot be maintained, the formation of such stars may be significantly less efficient.

The results may provide a new perspective on star formation throughout the history of the Universe.

This research has been published in the Astrophysical Journal on February 20, 2025, in the title of “ALMA 0.1 pc View of Molecular Clouds Associated with High-Mass Protostellar Systems in the Small Magellanic Cloud: Are Low-Metallicity Clouds Filamentary or Not?” by Kazuki Tokuda et al.

https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ada5f8

In ancient stellar nurseries, some stars are born of fluffy clouds (Kyushu University)

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an international astronomy facility, is a partnership of the European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO), the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS) of Japan in cooperation with the Republic of Chile. ALMA is funded by ESO on behalf of its Member States, by NSF in cooperation with the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) and the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) in Taiwan and by NINS in cooperation with the Academia Sinica (AS) in Taiwan and the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI).

ALMA construction and operations are led by ESO on behalf of its Member States; by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), managed by Associated Universities, Inc. (AUI), on behalf of North America; and by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) on behalf of East Asia. The Joint ALMA Observatory (JAO) provides the unified leadership and management of the construction, commissioning and operation of ALMA.

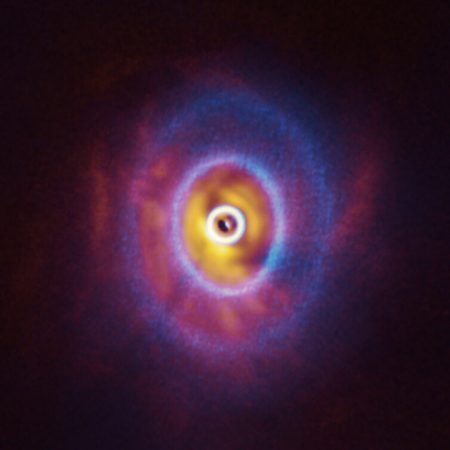

Fig. 1. Example of a filamentary (left) and fluffy (right) molecular cloud in the Small Magellanic Cloud captured by ALMA. The crosses in the middle indicate the presence of giant baby stars. The left figure shows a molecular cloud with a filamentary structure, and the right shows an example of a fluffy shape. Scale bar: one light-year. (Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), Tokuda et al.)

Fig. 2. Molecular clouds in the Small Magellanic Cloud. A far infrared image of the Small Magellanic Cloud as observed by the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Herschel Space Observatory. Circles indicate the positions observed by the ALMA telescope, with the corresponding enlarged image of the observed molecular cloud from radio waves emitted by carbon monoxide. The enlarged pictures framed in yellow indicate filamentary structures. The pictures in the blue frame indicate fluffy shapes. (Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), Tokuda et al., ESA/Herschel)