2019.01.10

What 30,000 Star Factories in 74 Galaxies Tell Us about Star Formation across the Universe

Galaxies come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. Some of the most significant differences among galaxies, however, relate to where and how they form new stars. Compelling research to explain these differences has been elusive, but that is about to change.

A vast, new research project with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), known as PHANGS-ALMA (Physics at High Angular Resolution in Nearby GalaxieS), delves into this question with far greater power and precision than ever before by measuring the demographics and characteristics of a staggering 30,000 individual stellar nurseries spread throughout 74 galaxies.

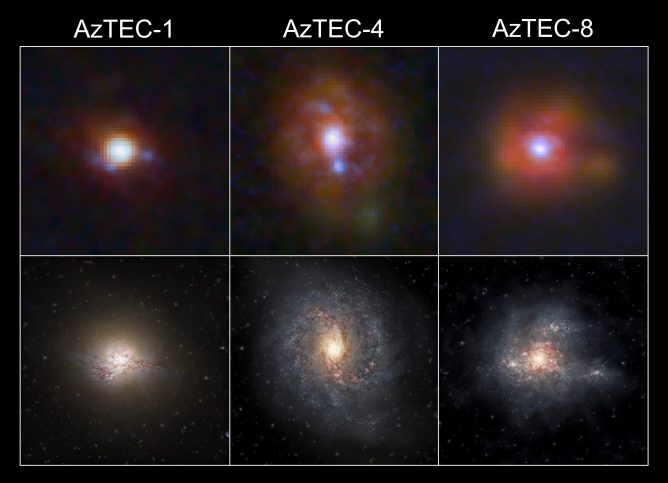

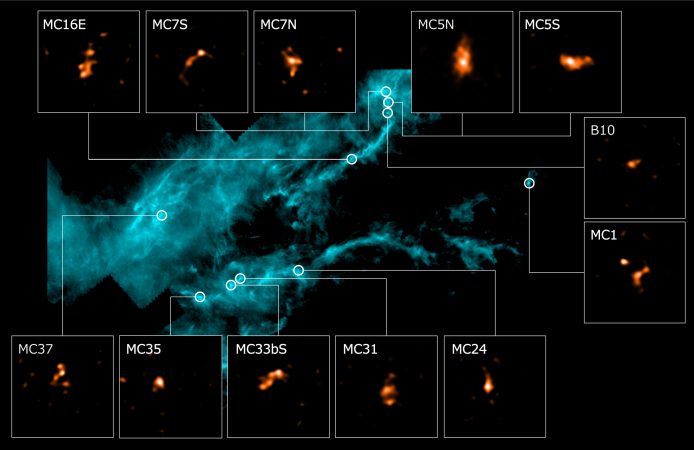

Six ALMA-imaged galaxies out of a collection of the 74. The images were taken as part of the PHANGS-ALMA survey to study the properties of star-forming clouds in disk galaxies.

Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO); NRAO/AUI/NSF, B. Saxton

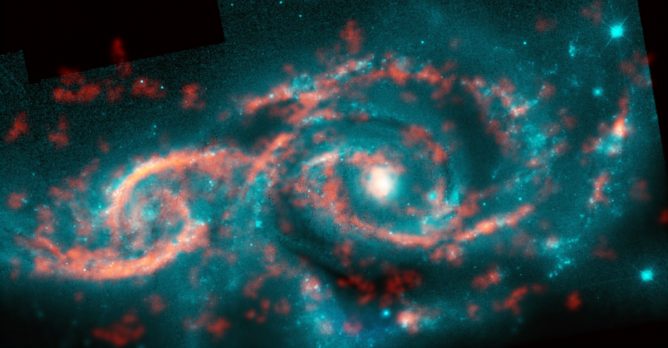

ALMA image of galaxy NGC 4321, also known as Messier 100, is an intermediate spiral galaxy located about 55 million light-years from Earth in the constellation Coma Berenices. It is imaged as part of the PHANGS-ALMA survey to study the properties of star-forming clouds in disk galaxies.

Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO); NRAO/AUI/NSF, B. Saxton

ALMA image of NGC 628, also known as Messier 74, a spiral galaxy in the constellation Pisces, located approximately 32 million light-years from Earth. It is imaged as part of the PHANGS-ALMA survey to study the properties of star-forming clouds in disk galaxies.

Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO); NRAO/AUI/NSF, B. Saxton

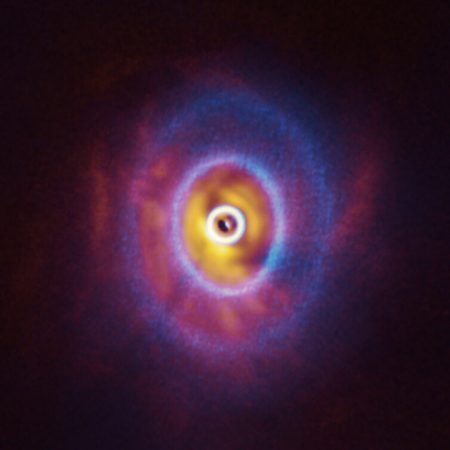

Composite ALMA (orange) and Hubble (blue) image of NGC 628, also known as Messier 74, a spiral galaxy in the constellation Pisces, located approximately 32 million light-years from Earth. It is imaged as part of the PHANGS-ALMA survey to study the properties of star-forming clouds in disk galaxies.

Credit: NRAO/AUI/NSF, B. Saxton: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO); NASA/Hubble

PHANGS-ALMA, an unprecedented and ongoing research campaign, has already amassed a total of 750 hours of observations and given astronomers a much clearer understanding of how the cycle of star formation changes, depending on the size, age, and internal dynamics of each individual galaxy. This campaign is ten- to one-hundred-times more powerful (depending on your parameters) than any prior survey of its kind.

“Some galaxies are furiously bursting with new stars while others have long ago used up most of their fuel for star formation. The origin of this diversity may very likely lie in the properties of the stellar nurseries themselves,” said Erik Rosolowsky, an astronomer at the University of Alberta in Canada and a co-Principal Investigator of the PHANGS-ALMA research team.

He presented initial findings of this research at the 233rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society being held this week in Seattle, Washington. Several papers based on this campaign have also been published in the Astrophysical Journal and the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“Previous observations with earlier generations of radio telescopes provide some crucial insights about the nature of their cold, dense stellar nurseries,” Rosolowsky said. “These observations, however, lacked the sensitivity, fine-scale resolution, and power to study the entire breadth of stellar nurseries across the full population of local galaxies. This severely limited our ability to connect the behavior or properties of individual stellar nurseries to the properties of the galaxies that they live in.”

For decades, astronomers have speculated that there are fundamental differences in the way disk galaxies of various sizes convert hydrogen into new stars. Some astronomers theorize that larger, and generally older galaxies, are not as efficient at stellar production as their smaller cousins. The most logical explanation would be that these big galaxies have less efficient stellar nurseries. But testing this idea with observations has been difficult.

For the first time, ALMA is allowing astronomers to conduct the necessary wide-ranging census to determine how the large-scale properties (size, motion, etc.) of a galaxy influence the cycle of star formation on the scale of individual molecular clouds. These clouds are only about a few tens to a few hundreds of light-years across, which is phenomenally small on the scale of an entire galaxy, especially when seen from millions of light-years away.

“Stars form more efficiently in some galaxies than others, but the dearth of high-resolution, cloud-scale observations meant our theories were weakly tested, which is why these ALMA observations are so critical,” said Adam Leroy, an astronomer at The Ohio State University and co-Principal Investigator on the PHANGS-ALMA team.

Part of the mystery of star formation, the astronomers note, has to do with the interstellar medium– all the matter and energy that fills the space between the stars.

Astronomers understand that there is an ongoing feedback loop in and around the stellar nurseries. Within these clouds, pockets of dense gas collapse and form stars, which disrupts the interstellar medium.

“Indeed, comparing early PHANGS observations with the locations of newly formed stars shows that the newly formed stars quickly destroy their birth clouds,” said Rosolowsky. “The PHANGS team is studying how this disruption plays out in different types of galaxies, which may be a key factor in star-forming efficiency.”

For this research, ALMA is observing molecules of carbon monoxide (CO) from all relatively massive, generally face-on spiral galaxies visible from the Southern Hemisphere. Molecules of CO naturally emit the millimeter-wavelength light that ALMA can detect. They are particularly effective at highlighting the location of star-forming clouds.

“ALMA is a stunningly efficient machine to map carbon monoxide over large areas in nearby galaxies,” said Leroy. “It was able to perform this survey because of the combined power of the 12-meter dishes, which study fine-scale features, and the smaller, 7-meter dishes at the center of the array, which are sensitive to large-scale features, essentially filling in the gaps.”

A companion survey, PHANGS-MUSE, is using the Very Large Telescope to obtain optical imaging of the first 19 galaxies observed by ALMA. MUSE stands for the Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer. Another survey, PHANGS-HST uses the Hubble Space Telescope to survey 38 of these galaxies to find their youngest stellar clusters. Together, these three surveys give a startlingly complete picture of how well galaxies form stars by probing cold molecular gas, its motion, the location of ionized gas (regions where stars are already forming), and the galaxies’ complete stellar populations.

“In astronomy, we have no ability to watch the cosmos change over time; the timescales simply dwarf human existence,” noted Rosolowsky. “We can’t watch one object forever, but we can observe hundreds of thousands of star-forming clouds in galaxies of different sizes and ages to infer how galactic evolution works. That is the real value of the ALMA-PHANGS campaign.”

“We also look at thousands to tens of thousands of star-forming regions within each galaxy, catching them across their life cycle. This lets us build a picture of the birth and death of stellar nurseries across galaxies, something almost impossible before ALMA,” added Leroy.

So far, PHANGS-ALMA has studied about 30,000 Orion Nebula-like objects in the nearby universe. It is expected that the campaign will eventually observe around 300,000 star-forming regions.

This news article was originally published by the U.S. National Radio Astronomy Observatory.

Papers

These observation results were published in the following papers.

Sun et al. “Cloud-scale Molecular Gas Properties in 15 Nearby Galaxies,” 2018, The Astrophysical Journal, 860, 172

Utomo et al. “Star Formation Efficiency per Free-fall Time in nearby Galaxies,” 2018, The Astrophysical Journal, 861L, 18

Kreckel et al. “A 50 pc Scale View of Star Formation Efficiency across NGC 628,” 2018, The Astrophysical Journal, 863L, 21

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an international astronomy facility, is a partnership of the European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO), the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS) of Japan in cooperation with the Republic of Chile. ALMA is funded by ESO on behalf of its Member States, by NSF in cooperation with the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) and the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) and by NINS in cooperation with the Academia Sinica (AS) in Taiwan and the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI). ALMA construction and operations are led by ESO on behalf of its Member States; by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), managed by Associated Universities, Inc. (AUI), on behalf of North America; and by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) on behalf of East Asia. The Joint ALMA Observatory (JAO) provides the unified leadership and management of the construction, commissioning and operation of ALMA.